Testing ML Models in Production

Problem

Introduction

Testing is an important part of any production software. Without it, simple mistakes which developers didn’t mean to make, seep into production and can be the result of lost revenue, unmet SLAs, etc.

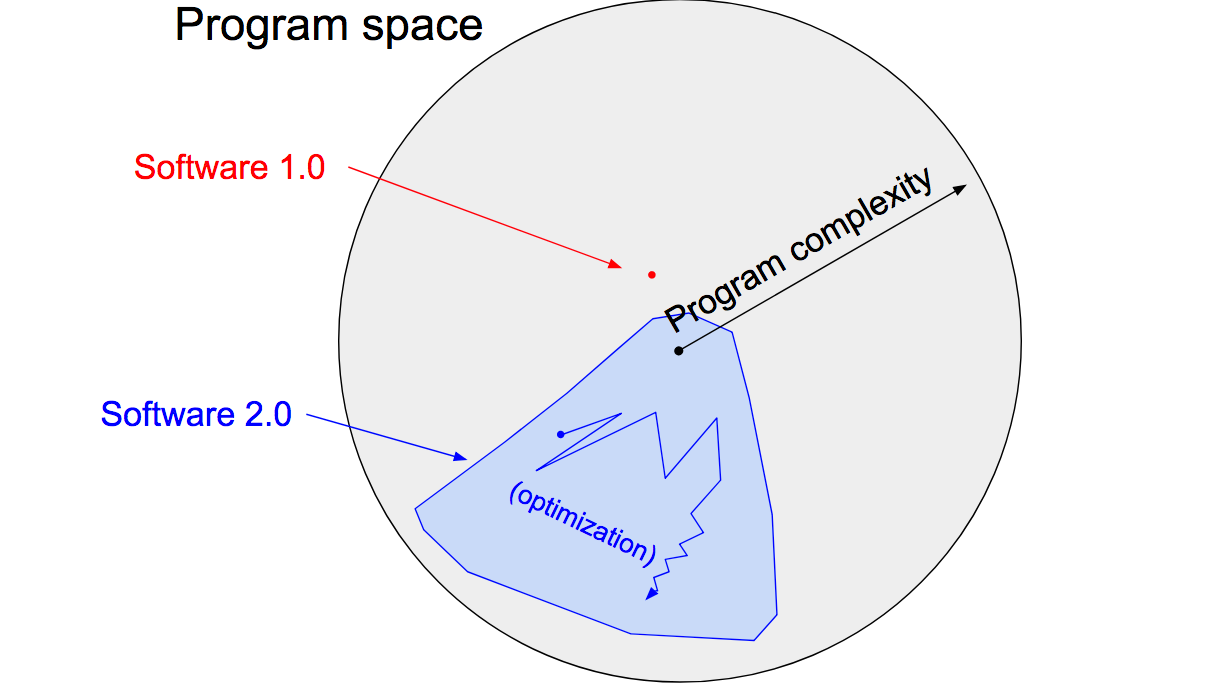

One universal practice software developers follow is unit testing and continuous integration where a test suite is run against the whole codebase everytime something is committed. This is a majority contributor to finding failures before moving to production. This type of testing however only works on what we call the Software 1.0 stack.

Software 1.0 is being replaced and ML models are already the major contributor. Instead of writing code that solves a problem, we’re writing code which trains a model which solves a problem. This is called Software 2.0.

Our workflow changes from write code, test code, deploy code to collect data, label data, train model, evaluate model, tune hyperparameters or curate dataset, repeat, deploy. The later part of this new process is where things get a little hand-wavy. What are the most important metrics to evaluate on? What should we change to improve model performance? Autonomous driving is a perfect example of why this is really hard. You could build a great prototype for a self-driving car in 2015 with little budget (Comma AI did this). But 5 years and billions of dollars later, the best autonomous driving systems are still ~L2+ (see this).

When it comes to evaluation, ML practitioners tend to pick one or two north star metrics and stick with those for the rest of their project. This could be their aggregated cross-validation score on a validation set, or a different score on a held out test set, or just manually evaluating on individual samples and visually evaluating. One important thing to note though is that all these metrics in an ideal world are trying to represent one thing: how well will our model do on data it has never seen before, in the real world? This is a constant struggle of building the flashy ML demo into something that works in production.

Autonomous driving is the seminal example of this and has been the field that has helped most with the development of new ML algorithms but there are bound to be dozens of other applications of the same scale with the same high stakes. The billion dollar question will be how we can bring the prototype to production cycle down from unknown (since AVs are still not solved) years to just one or less.

Evaluating correctly and being able to surface exact failure patterns allows for the right data to be labeled next, and for a team to know whether a system is production ready.

Test-Driven Development

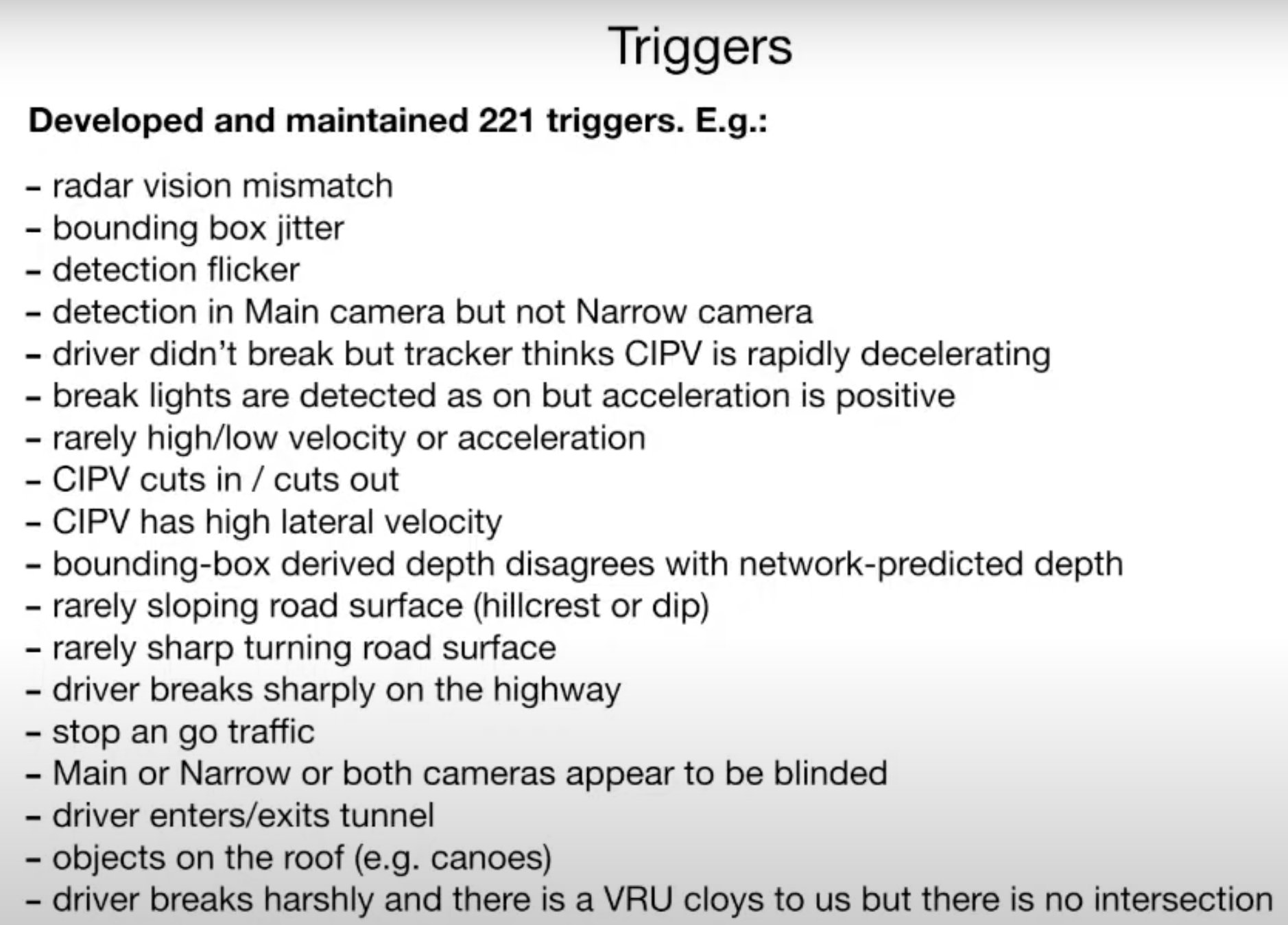

This is where we might want to take inspiration from test-driven development philosophies which have worked flawlessly as we’ve built some of the most sophisticated software systems. At its core, it means the following (a slide taken from Tesla’s Andrej Karpathy):

Just like with software, let’s come up with a set of cases, or critical populations of data, that we can separately evaluate our model on (before we ever train a model). If it passes each of these tests separately, it is ready for deployment. This in-fact is what most top-notch ML projects follow and is regarded as a gold standard as per what teams want to bring to their model evaluation.

The problem arises when teams try to compile a meaningful set of critical populations of data which makes sense to evaluate on. After all, there are infinite edge cases and no way to test all of them.

Current Solutions and Issues with Them

One way teams implement this today is through access to external data. This could be through a set of sensors or some other extra data which can be used as hindsight. An example of this could include an extremely heavy ML model which can’t be run in production but can be run in evaluation to provide more accurate results we treat as ground truth. This allows one to make simple classifications like “pictures with more than 5 people”, “pictures with less than 30% road”, “sequence where bounding box flickers”, “sun glare”, etc. These are then used as the critical populations to evaluate on.

Let’s discuss the issues with this.

First is the engineering time that goes into putting systems in place which detect sun glare, or include other types of evaluations which aren’t directly related to the problem / are too heavy to use during test time. What if you want to evaluate on a set for all images where the sun is about to set? This “sunset” characteristic hasn’t been labeled and can’t be detected trivially by a sensor. This highlights the fact that not all relevant “critical populations” are necessarily just what is labeled in your data or is detected by your main system. Most of the time, external unlabeled factors influence a model in more significant ways than paid attention to.

Second, what if new data is constantly coming in and there are new edge cases to potentially explore and automatically add to the evaluation suite? There is a lot of boring, annoying code to write to make this work seamlessly.

Finally, who likes writing tests anyways? Many bureaucratic companies force their software teams to do this but many fast-growing startups don’t have strict requirements due to the pace of change. With regular software, it’s hard to automate the creation of tests. With ML, there is at least some hope for making it easier to automate a test suite.

What to Solve

At its core, we want to build an easy way to do test-driven development in production ML with datasets. This means making it easy to find critical populations through some sort of query language. We’ll focus on computer vision first.

Solution

The first part of a solution is a tech stack that allows users to easily search for data. In the context of images, it could mean any of the following things.

CLIP for text searches on a dataset of images?

“Windy road with no trees”

“Dimly lit factory floor”

“Ocean view on a bridge”

Search by image? Use one image to find similar images to add to a set using embeddings.

Click on an image of a bathroom –> set of many bathrooms

Click on an outdoor image of a forest –> many forests

Automatic classification, detection, segmentation models run on data for metadata search?

SELECT image, num_people

FROM dataset

WHERE num_people > 5 and weather = ‘sunny’

SELECT image_name

FROM dataset

WHERE road_pct < 0.1 and ocean_pct > 0.7

This searching stack should then be a part of a managed platform which can automatically run the required models for automatic data tagging and neural network based embedding or text search. Searches should either be able to be made via a web UI or a Python API.

Along with the searching stack comes organization into different sets/groups that can be used as unit test sets. A set of training / testing samples can then easily be pulled using the Python API as a part of a team’s training / evaluation code.

Example Workflow

Data either exists in some system, or is in a bucket in the cloud. Regardless, that bucket can keep updating as more data is collected and acts as the place for all your raw collected data (maybe with labels included). It is somehow hooked up to the managed platform.

Use the managed platform to write queries for interesting populations of data (see Solution section). Give the query a name and choose a percentage of this type of data that you want to add to a hold-out test set.

See the percentage breakdown of how much data in training, test, and validation sets fit / do not fit into each of these categories.

Use Python API to upload evaluation scores / predictions for each sample and automatically visualize across different interesting populations.

See subsets in which model is performing poorly to narrow in on failure patterns. Then, either apply new pre-processing, post-processing, or collect new data to improve on that subset.

Make new queries easily and see whether there is drastically low performance on any of them. If so, it might be important to add that as another unit test.

Core Value Adds

Have 10x better insight into where model is performing good/bad

Spend less time model debugging and spend more time improving Better communication with relevant stakeholders past arbitrary accuracy/f1 scores More self-aware product experience depending on model performance issues

Have 10x better oversight over collected data

It is expensive to get all data labeled, tagging provides visibility over the type of data you have and type of data you need As troves of data get piled, having information that doesn’t have to be self-transcribed becomes extremely important

Potential Initial Target Markets

Logistics companies handling documents

AV companies

Companies deploying algorithms on IP cameras

Other Related Projects

https://www.amundsen.io/amundsen/

https://kolena.io/